At Magnolia, one of our core values is cultivation. This means we create an environment where new ideas, opportunities, and innovation thrive, which benefits both our team and the clients we serve. This value inspired the theme of our May 2019 staff retreat: intentional cultivation. During our four-day retreat, the team unexpectedly cultivated a second theme—using a common language. It emerged most prominently in two of our sessions.

Using a common language to improve our processes

On the first day of our retreat, Lisa Cooper Ellison, a Charlottesville writer and editor, provided a half-day workshop on writing best practices. Initially, we thought we would learn tips for writing more clearly and succinctly, but the workshop ended up being about so much more.

Lisa shared the biggest takeaway within the first few minutes of the workshop:

In order to work more efficiently as a team of writers, we needed to develop a common language for approaching the writing process.

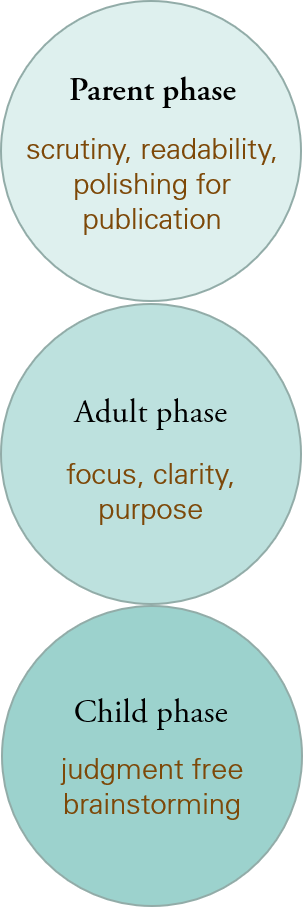

She introduced us to three phases in the writing process: the child, parent, and adult. The phases come from Dinty Moore’s book The Story Cure, and while this book is geared towards creative nonfiction writers, the phases are applicable to a variety of settings. In the child phase, we work to nonjudgmentally brainstorm ideas. Then the adult shapes those ideas into a clear message. Finally, the parent polishes the work for publication.

As a team, we review each other’s writing in either the adult or parent phase. In the adult phase, we ensure the writing has clarity and is meeting its intended purpose. In the parent phase, we examine the writing for logic flaws, jargon, and the accuracy of our content. During the workshop, we discovered we weren’t leaving enough room for the child phase which is where many of our best ideas come to life. We also realized the importance of explicitly communicating our needs when sending our work to others for review. For example, if the writer is still exploring new ideas and creative avenues (child’s phase) this information must be shared with the reviewer. Otherwise, she might not keep her parent’s eye (which tends to line edit) shut.

Using a common language to solve problems

On the third day of our retreat, we went to Triple C Camp, a local camp that provides team building workshops. We played several fun and challenging games that helped us learn more about ourselves as individuals and how we work together. During one of these games, we discovered that the most effective way to address our challenges was to develop a common language. We separated into two teams and competed to see which team could re-create a Lego sculpture most accurately. Only one person on each team could see the model sculpture. That person shared instructions about the size, color, and orientation of each Lego piece making up the sculpture to the next person. These instructions were passed down the line telephone-style, and the last person had to put the Lego piece in the correct spot. Because we developed a common language to describe each piece and its orientation, we came closer to replicating an identical sculpture than any other team in Triple C Camp history!

Using a common language whenever possible benefits our team. Moreover, there is a clear connection between communication and intentional cultivation. When we develop a common language around our activities, problems, and processes, we are more intentional about how we work as an organization.

Every year we leave the retreat grateful for the opportunities to connect, have fun, and cultivate learning together, and this year was no different!